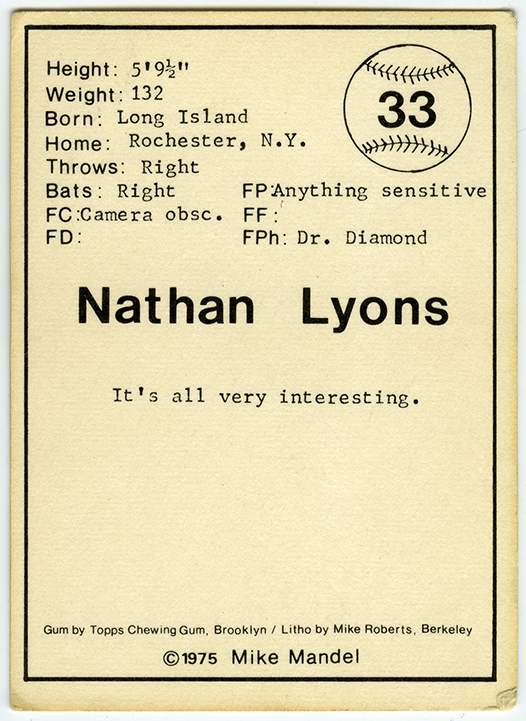

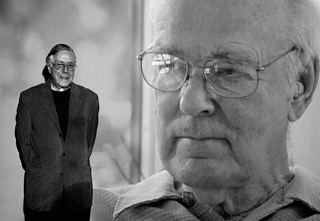

Exhibitions Nathan Lyons

(1930-2016)

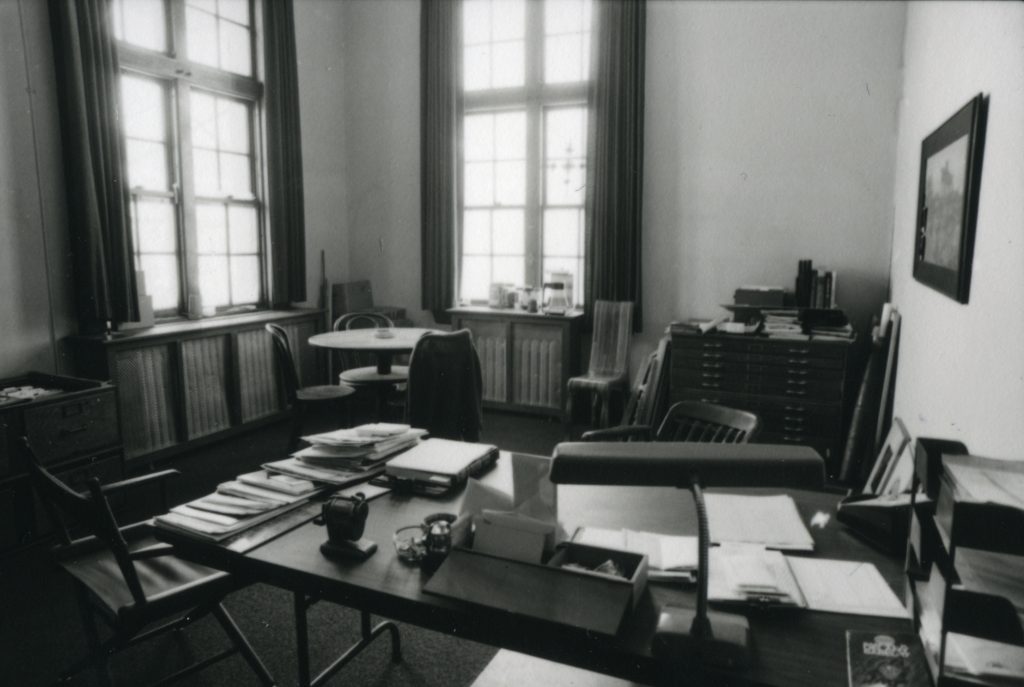

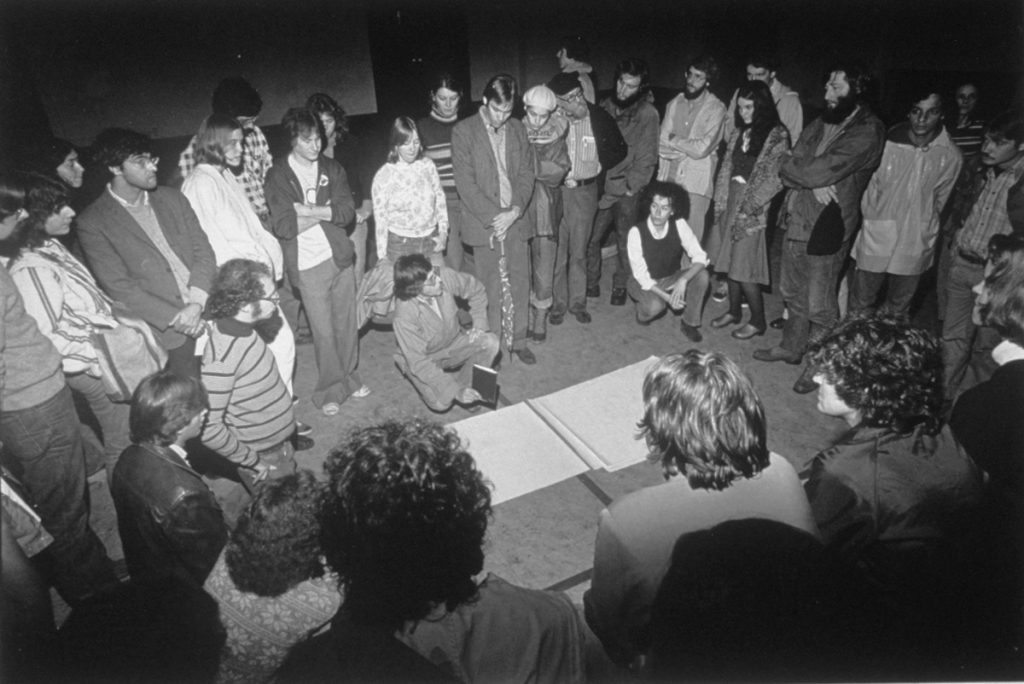

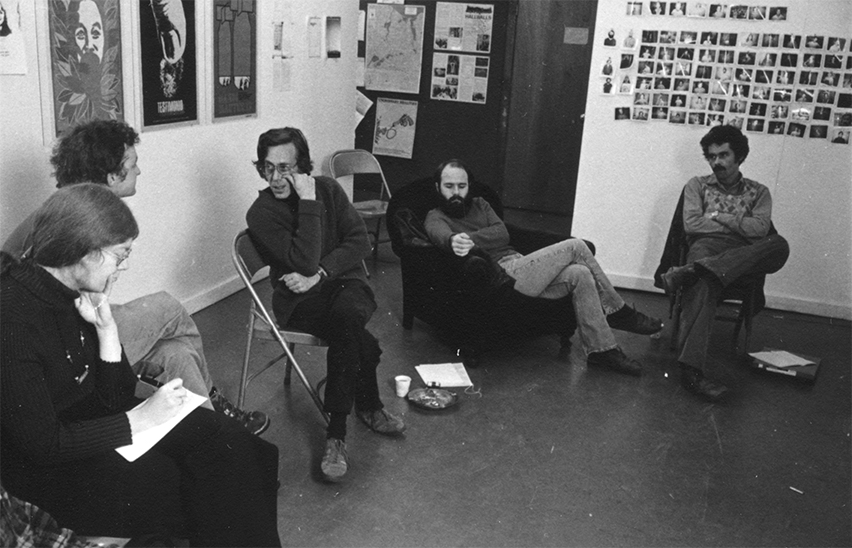

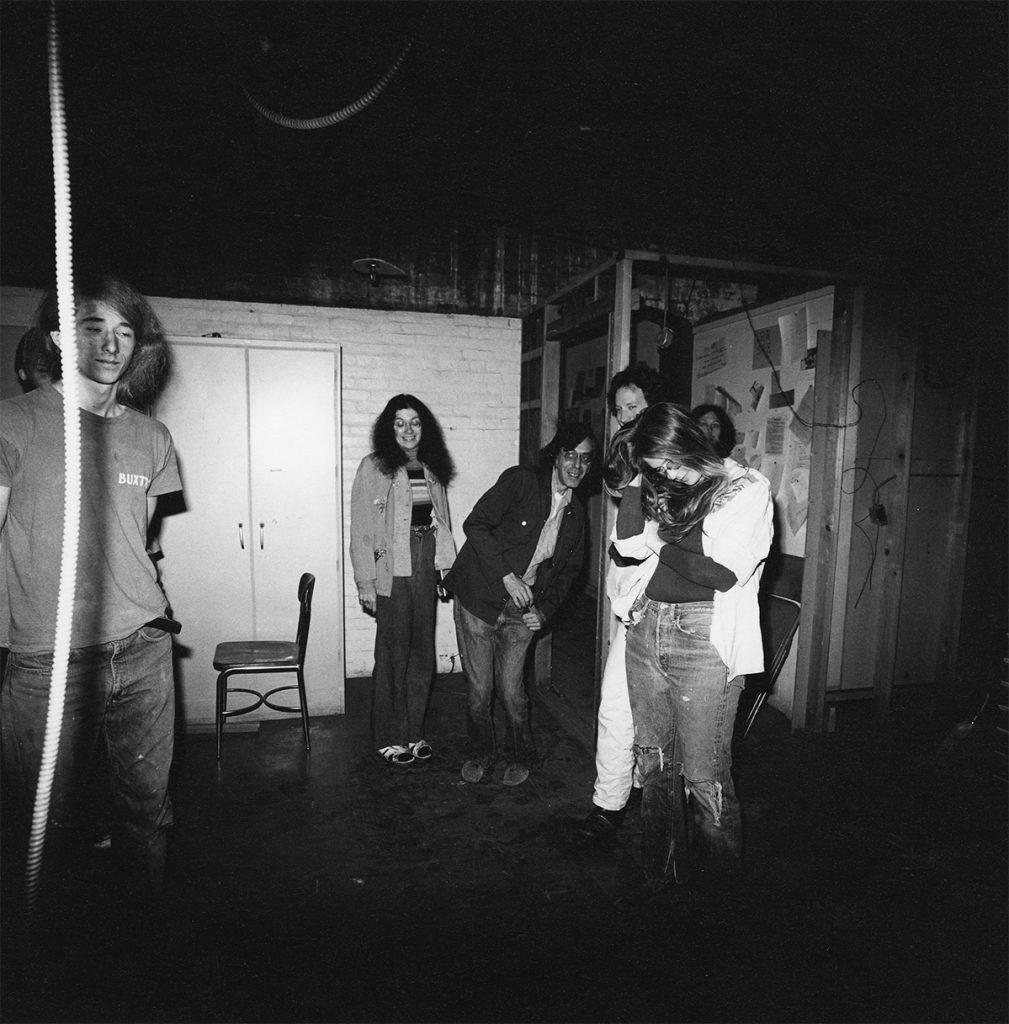

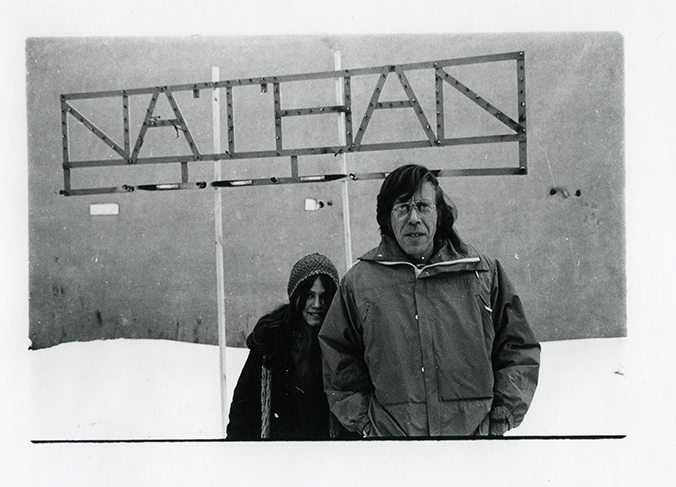

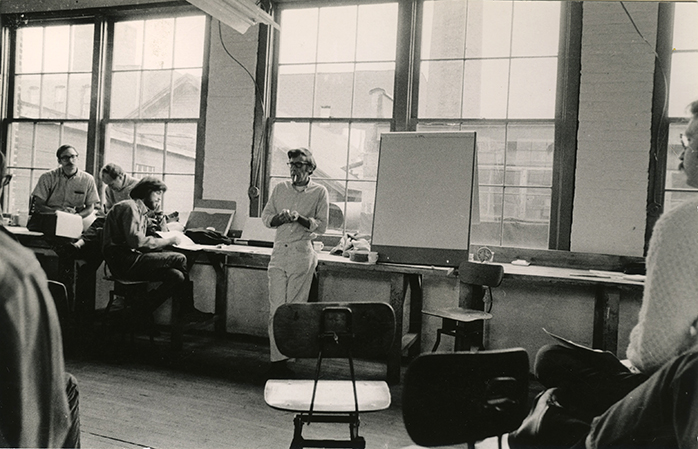

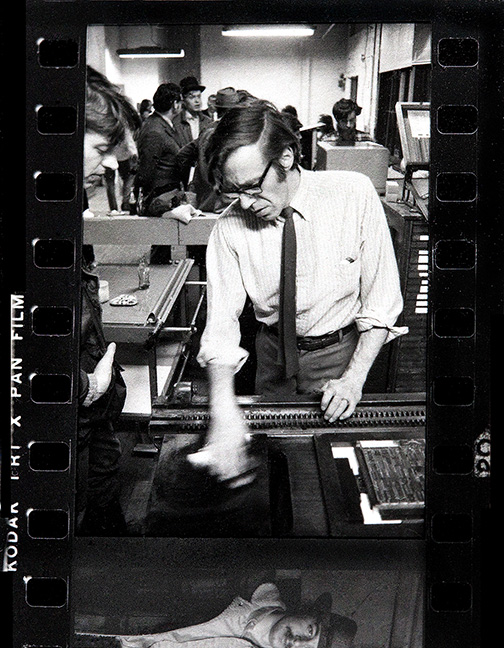

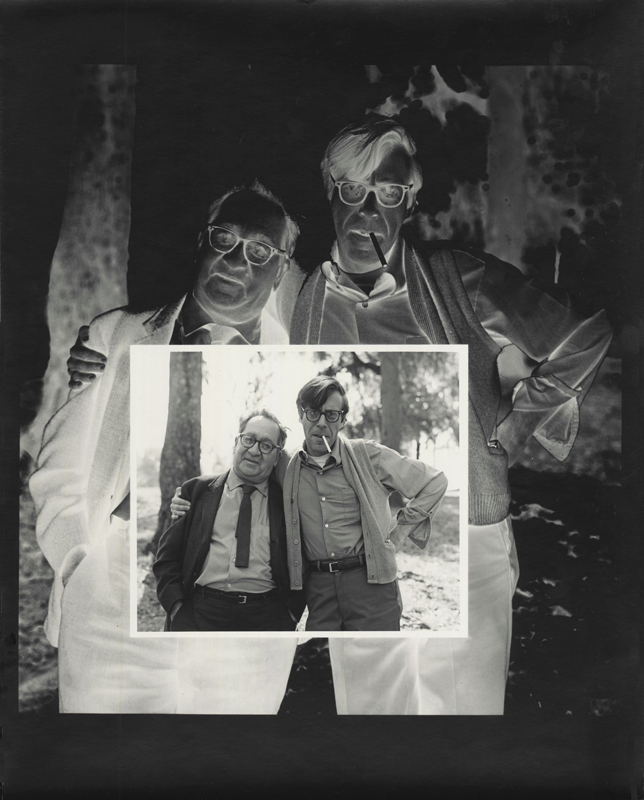

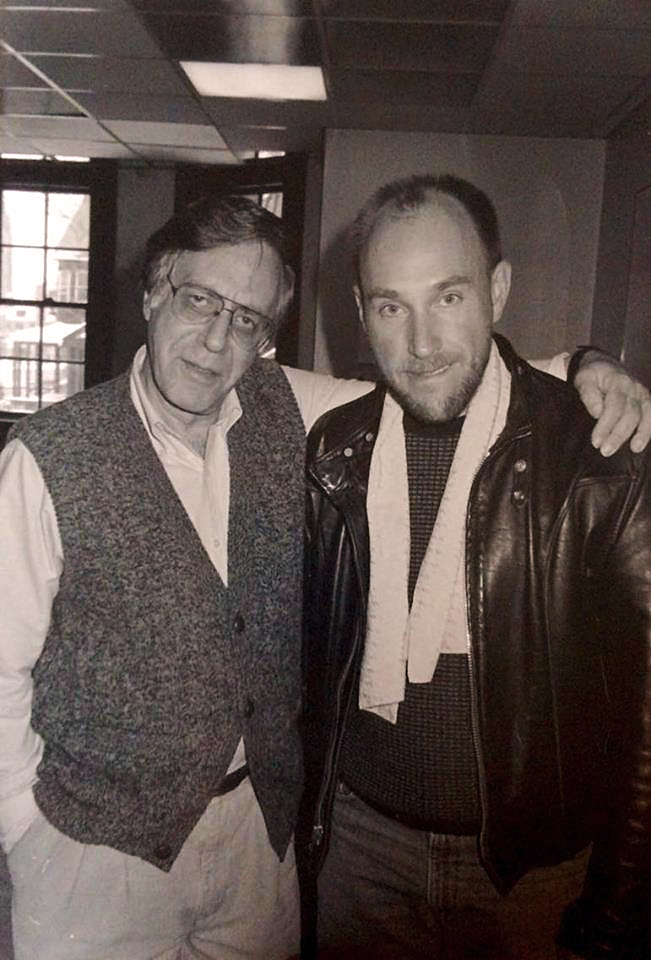

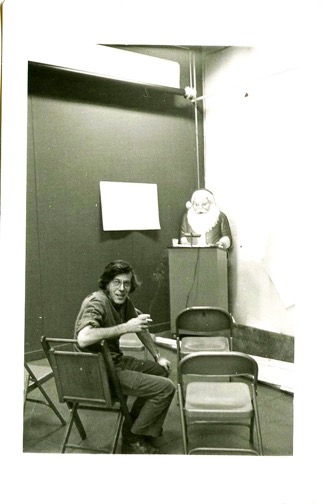

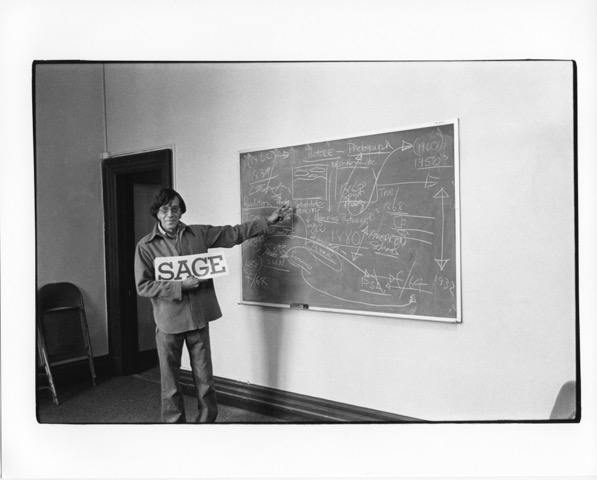

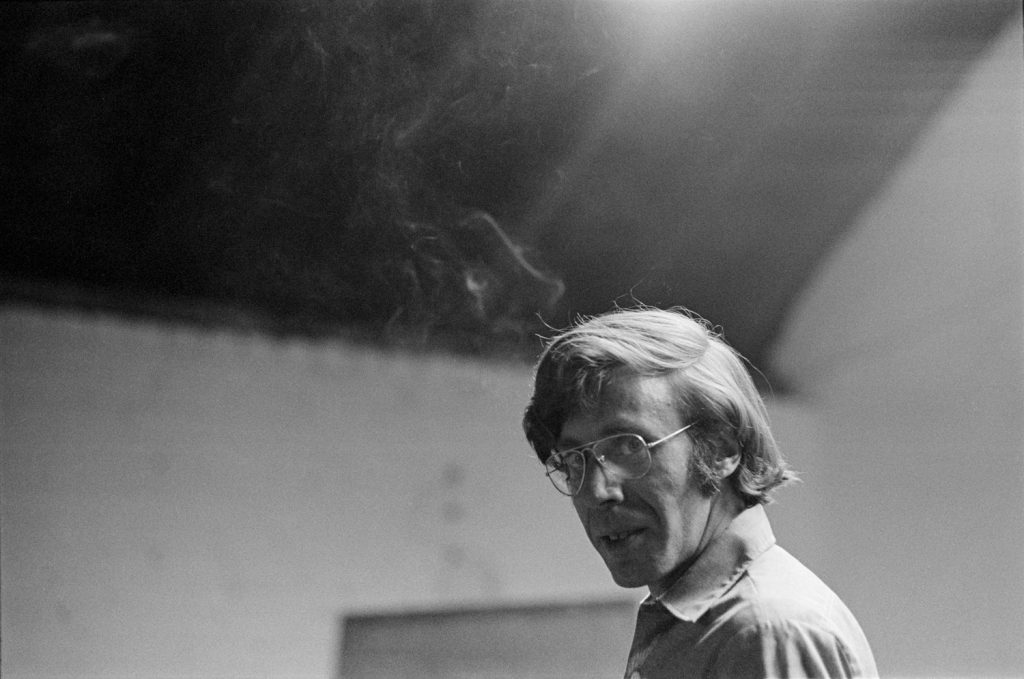

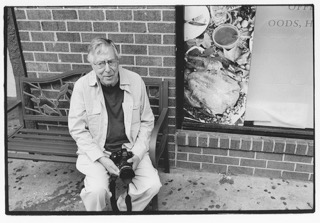

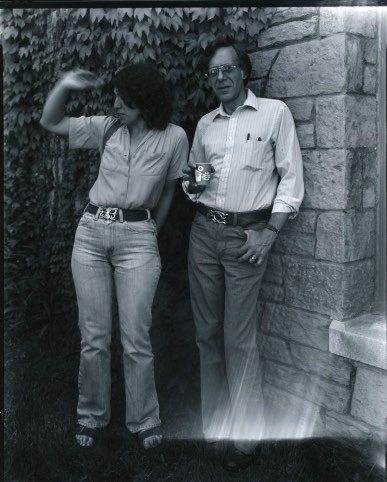

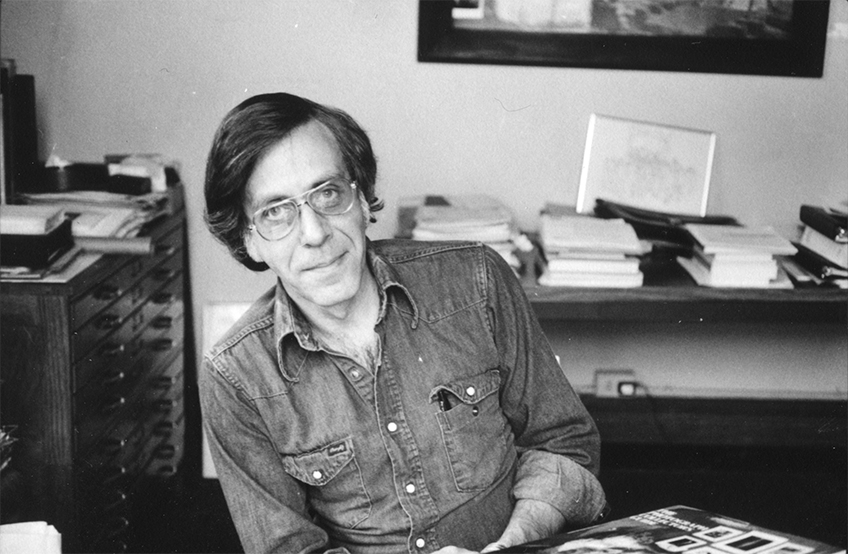

at VSW, ca. 1980, attributed to Alice Wells

at VSW, ca. 1980, attributed to Alice WellsIn memory of Nathan Lyons (1930-2016)

The Lyons family has asked that donations in Nathan’s memory be made to Visual Studies Workshop where the Research Center collections and library will be named in his honor.

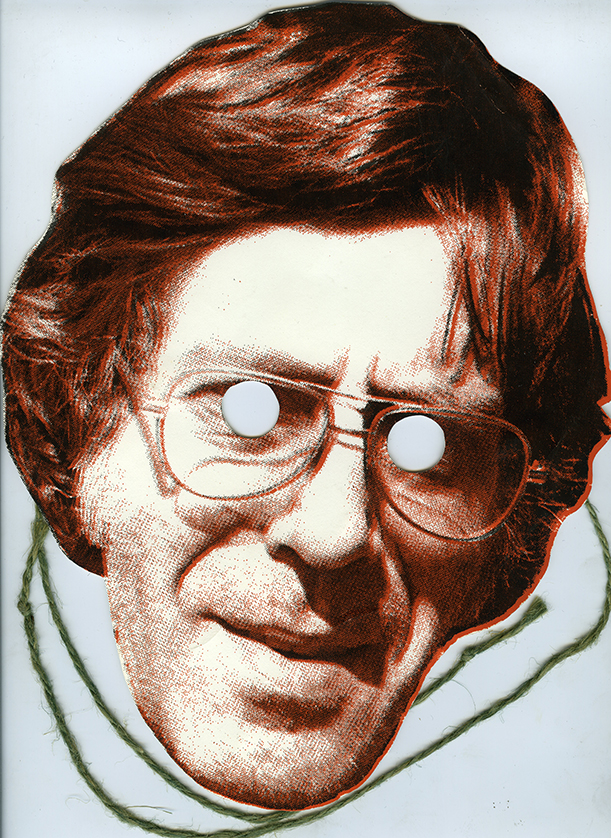

Nathan Lyons, 1930–2016: A Remembrance

by Jessica S. McDonald

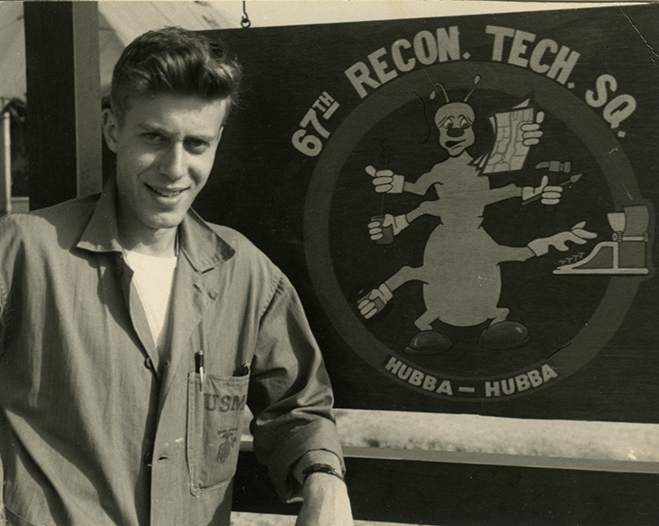

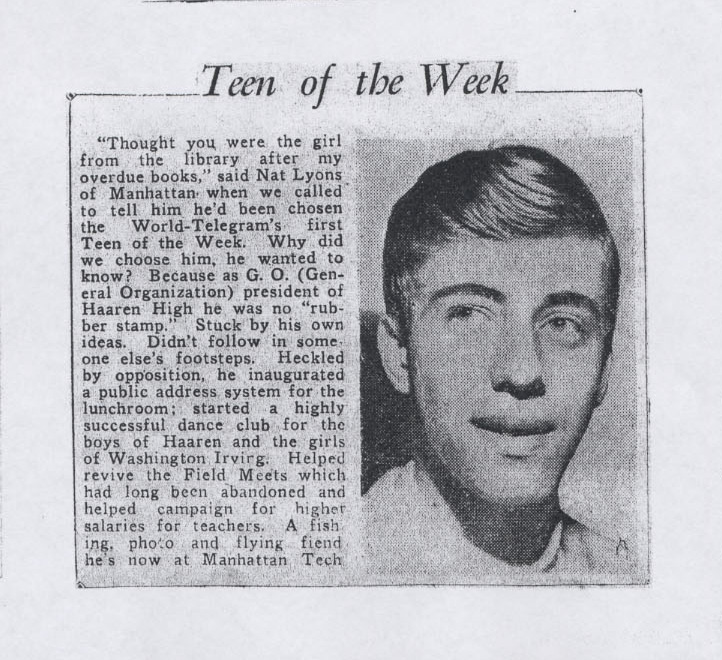

Nathan Lyons laughed each time he was reminded of this 1947 New York World-Telegram clipping naming him the newspaper’s very first “Teen of the Week.”

Read More

Read MoreNathan, class president at Haaren High School in Manhattan, evidently earned the honor for his principled stance on important issues—such as whether or not the lunchroom should have a public address system—and for campaigning for increased teacher salaries. “Nat Lyons,” according to the short feature, was “no ‘rubber stamp.’ Stuck by his own ideas. Didn’t follow in someone else’s footsteps.” Young Nat’s activist streak will be familiar to anyone who knew Nathan the visionary leader. As an artist, curator, theorist, educator, and powerful advocate, he was one of the most important voices in American photography for nearly sixty years. He was also a husband, a father, and a grandfather, a dear friend and a mentor. He was a remarkable human being.

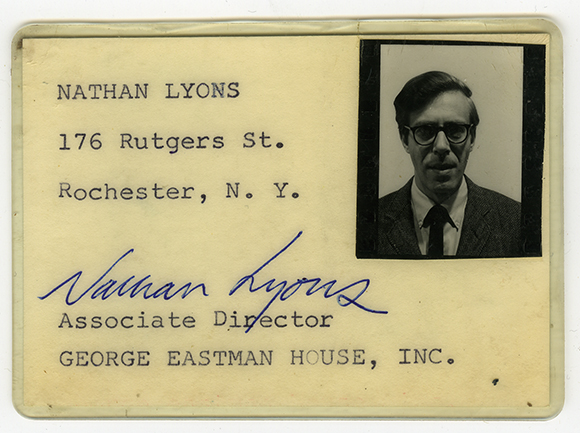

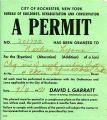

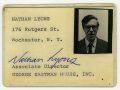

Nathan’s tendency toward trailblazing was an essential component of his success when he arrived in Rochester in 1957 and landed a job at George Eastman House. He imagined a future for photography, outlined what needed to be done, and quietly got to work. He immediately understood the importance of forging networks such as the Society for Photographic Education, and of simply introducing people who would benefit from knowing one another. He also organized some of the most provocative and far-reaching exhibitions of his time and through them, and their related publications, built an audience for contemporary photography. He told Photo Metro in 1989, “One of the things that I was very committed to was the work of the younger generation of artists. The basic feeling was that they needed support, they needed encouragement.” Nathan frequently spoke about commitment, support, and encouragement. He led by example, working long hours with few resources, and demanded no less from his staff. When photographers were frustrated about the state of the field, he instructed them to get to work too.

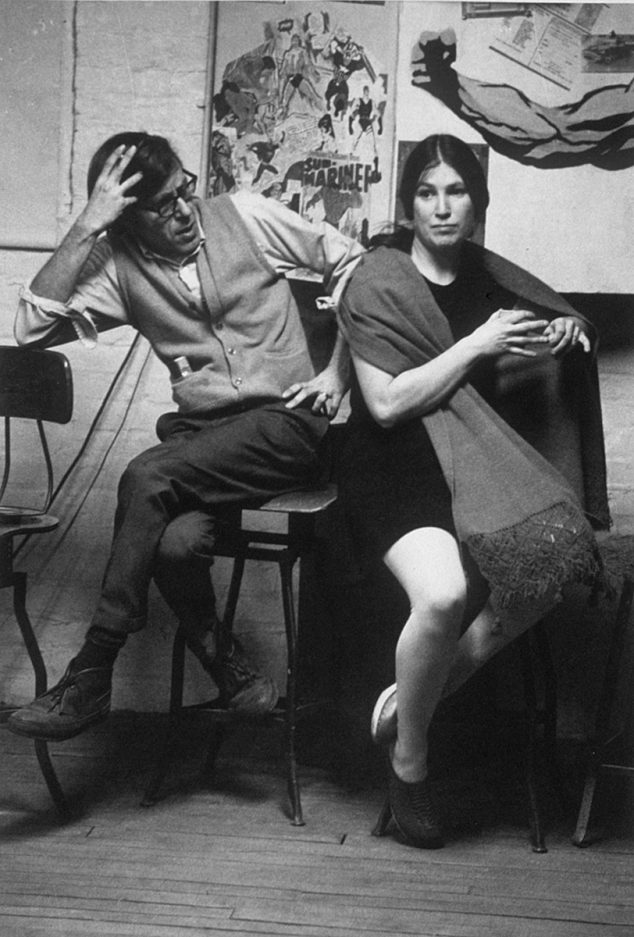

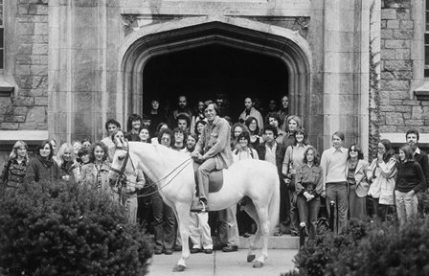

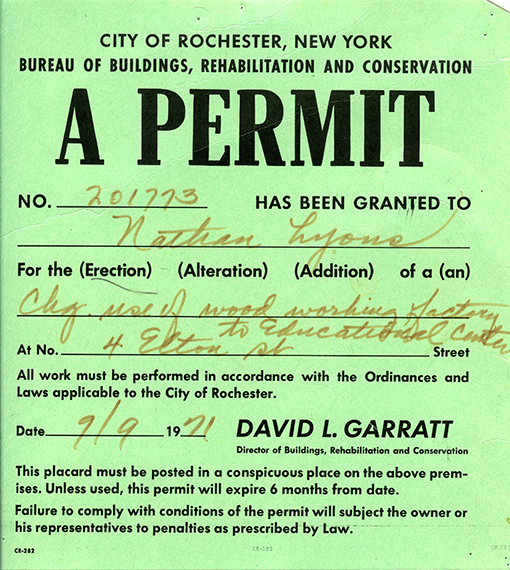

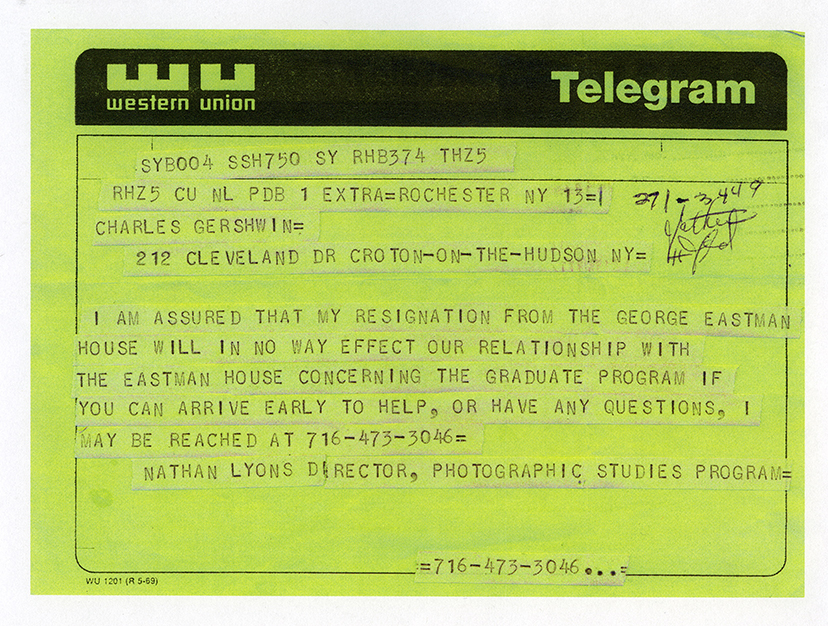

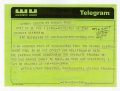

It was a matter of principle that eventually led Nathan to leave his post at the Eastman House in 1969, and to found the Visual Studies Workshop, a not-for-profit, artist-run, educational organization that was simultaneously a graduate school, publishing house, exhibition and performance space, commercial gallery, museum training ground, and community center. “This by no means will affect my commitment to the medium,” he wrote to Museum of Modern Art curator Grace Mayer about the abrupt transition. “It may make things a little more difficult to proceed, but I am willing to extend what personal energies I have on behalf of concerned people.” Those who had respected Nathan’s efforts at Eastman House now rallied around his vision for the Workshop. In the spring of 1970, a fundraising exhibition simultaneously held at the Workshop and six galleries across the country brought in over 3,000 prints donated by Nathan’s network of friends and supporters. He later recalled being heartened by the tremendous show of confidence.

When students showed up for classes at the Workshop, they quickly learned that their “work” would include cleaning, repairing the building, and getting the whole operation ready for the new school year. Nathan explained in a 1976 interview, “Everything that’s involved is important…. I can possibly reach a student here over a hammer and saw more directly than in a conventional classroom.” This is one way that students developed a sense of ownership of the program, and membership in their new community. The environment Nathan created was one of free expression and independent thinking, with a strong foundation of integrity, tolerance, accountability, and social responsibility. He instilled in participants a commitment to “the field,” even as that became increasingly difficult to define. His students went on to become leading curators, museum directors, critics, educators, and of course photographers, carrying Nathan’s philosophy with them. “They went out and they did wonderful things,” he said in a 2013 interview. “And that to me was what it was all about. Not what I did, but what they were doing. But I left a little piece for me, off to the side.”

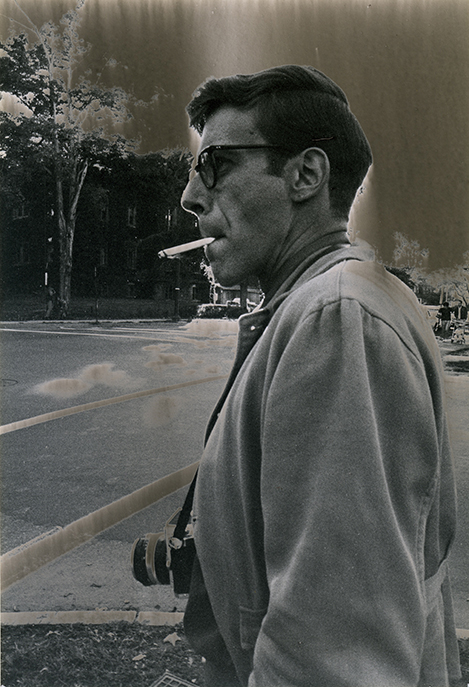

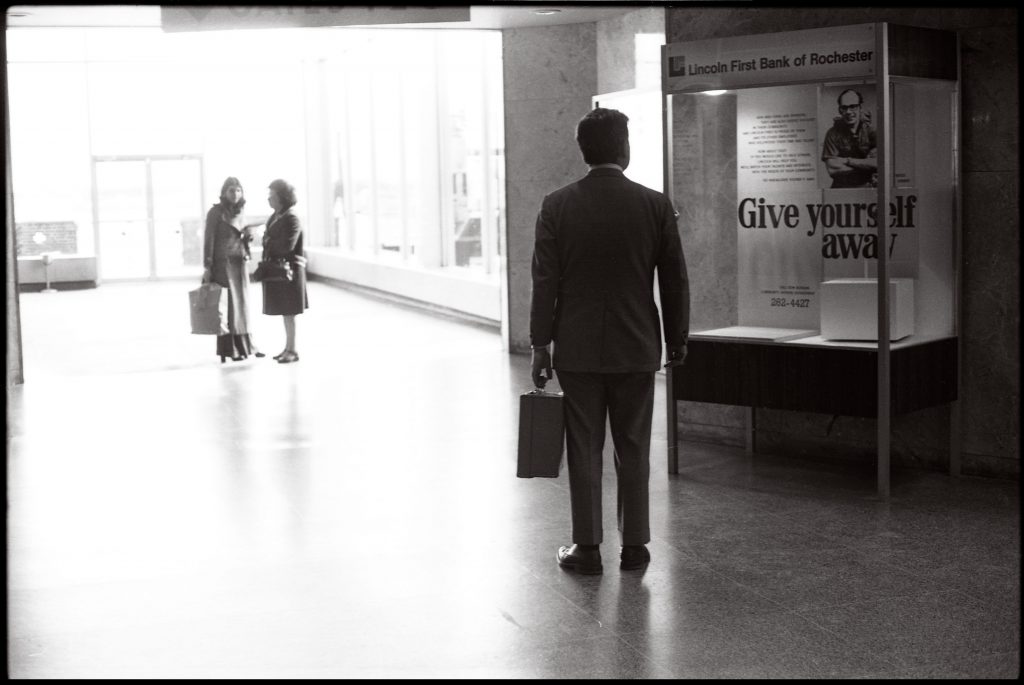

With what little time he had “off to the side,” Nathan published four books of his photographs. The first was Notations in Passing in 1974. Its ninety-seven photographs presented public visual display—posters, advertisements, shop windows, and billboards—as a complex form of social communication at a time when such signs typically eluded serious consideration. Significantly, with Notations in Passing Nathan articulated his ideas about image sequence and book structure. A few years later, in an obscure artist’s statement, he provided a few hints for those who hadn’t yet made sense of it: “If metaphor is a verbal strategy to evoke images, then as a photographer I’m interested in combining images to alter associations by extending the image itself. A juxtaposition of images enhances this possibility, while an extended sequence of images establishes a highly interactive structure that does not simply identify objects or events in a narrative sense but transforms the meaning of objects. It is this act of transformation, interactively between images, that I find most challenging.”

Nathan advanced his approach to photographic books, as well as his pointed cultural examination, with Riding 1st Class on the Titanic! in 1999, After 9/11 in 2003, and Return Your Mind to Its Upright Position in 2014. The succession of books functions as an extended journal, tracing his evolving concerns as he moved through life. In the last book, one pair of images in particular suggests a visual rumination on mortality. On the left, a rocking chair appears to be surrounded by a roll of wire fencing. On the right, a message stenciled on a brick wall reads “RECLAIM YOUR LIFE.” During a public program he was asked to elaborate on the meaning of this diptych, projected on a large screen. He pointed out the association of rocking chairs with aging and stated simply, “when you get past eighty, you think about reclaiming your life.”

I first met Nathan ten years ago, after he had retired from the Workshop and “mellowed out” a bit, as I was repeatedly told by his former students. It took a while to decode his conversational style. His old friends already knew to wait for the almost smile, the tilted eyebrow, and, eventually, the measured statement that cut right to the heart of the issue. He was busy with publishing projects and exhibitions, and was enjoying his first real foray into color photography. I suspect that he spent a great deal of the past decade patiently listening to the legions that sought his wise counsel. A good talk with Nathan could quickly put one’s priorities in order and mission back on course. “Proceed,” he advised, even when progress meant ruffling a few feathers. “Being a provocateur has its advantages,” he told a crowd at the Center for Creative Photography in 2013. “If you see something that you don’t feel is right, you should speak up about it. You should do something about it.” He added firmly, “If I had it to do all over again, I wouldn’t have changed a damn thing.”

Jessica S. McDonald is the editor of Nathan Lyons: Selected Essays, Lectures, and Interviews, and chief curator of photography at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas.

by Ethan Lyons

Remarks from the Celebration of Nathan Lyons at VSW on November 19, 2016:

This is as much a tribute to a place and to all of you as it is a memorial, or better yet, a “celebration” of the life and work of Nathan Lyons. On behalf of my family, I want to express how much we genuinely appreciate your love and support, and we especially thank you for being part of Nathan’s life.

Read MoreMy dad connected with so many people on so many levels in so many ways, it would be impossible to sum that number up, nor to tell all of the stories in this place right now. He is well documented in his work and in his decades as an Artist/Educator/Historian, and Champion for the Arts. Nathan’s contributions to the arts were numerous, important, and generous. You already know what Nate has done and/ or have some personal connection of your own to his amazing legacy as a thinker. Rather today, I would like to share with you some of the lessons and sage advice I learned growing up in our home and around the Visual Studies Workshop (which were often one in the same) and around most importantly, Nathan.

Nathan was a positive man. He was fearless. While Nate may have had reservations about the current state of the World, he was never shy to investigate its’ “possibilities.” Founding a truly Pragmatic school of education, in the time my parents did, was a miraculous undertaking. No doubt about it; Nathan had, “chutzpah.” Joan and Nathan grabbed an amazing dream and turned it into a great reality. They did not fear the world. Because of this, their hard work and forward thinking, they built a community and a place where it was safe to make art.

Knowing this (and just plain not having much other choice as a kid) I would walk over to the VSW on Elton Street after school when I was about 7. It was 1972. I learned some amazing things. Printmaking, photography, running the letterpress, using the porta-pack to record video, typing address labels, looking at books in the research center, chattering with people when I suppose they were trying to get work done; it was all very exciting and very natural learning this way. It was a veritable artistic playground filled with kind and creative people. I have very fond and vivid memories of running around the place, very excited to learn, to make things, to see what was being made, and to talk with some really incredible people. These are the best kind of memories a person can have. Many of you who are here today may remember as well. For those of you who I tormented, you will be happy to know that I now work in an art room each day with kids as young as 5, so my karma has caught up with me. I apologize now if I ever kept you from your work! Kidding aside, I really and truly want to thank Nathan for making such a special place in the world and thanks to all of you for being a part of it as well. What a great way to learn.

I still use the lessons of the early days at VSW and also I use the wisdom that Nathan imparted in me. First and foremost, Nathan taught me vocabulary. He had an amazing vocabulary and sometimes he had the trickiest way of improving mine. I’m not sure if he was aware that it even happened, but it’s funny to think about. You may remember, he had this superhuman ability to use the utterances, “uh” or “um” in addition to the usual prepositions. I remember going to some of Nathan’s slide presentations and lectures at a really early age and literally counting the “uhs” and “ums”, stupidly avoiding the content of what he was saying. Instead of hindering my ability to understand things, this tendency of his actually improved my word retrieval.

“Hey Eth…. could you go down to the uhh… the.. uhh…umm” ,

“Store?”

“Yeah, the store, and get uhh…. uhm… uhhh”

“Some cigarettes?”

“Yes, some cigarettes.”

I think it might have been a preoccupation of his mind, or even that he used that space to think of even better possibilities of what to say, but regardless he taught me vocabulary in this way from a very young age.

When I left home for school at 17, I remember Nate was serving on Jury Duty. I asked on my way out the door, “Dad, do you have any final advice before I leave.”

He looked at me very thoughtfully and said, “Avoid a jury of your peers at all costs.” That was pretty sound advice and I pretty much use that as a touchstone today. Don’t do anything in your life that will subject you to all that subjectivity… unless of course it’s making art. Hmmm… I may just use that line on my own daughter Ella when she is old enough to move away.

Even today, I have developed a teaching style that is in part, based on Nathan’s responses (and lack of responses) to others. I studied him for years as he worked with people and as he reacted to the questions I would inevitably bring to him. I know there was a lesson there. When posed with a question there were often 3 possible responses… regardless of the question: One, “a total lack of a response.” Two, “That has possibilities.” Last, the much sought after, “That’s interesting.”

In the first case, I may have said something he thought was a really bad idea or something far off base in terms of my thinking. In this instance he would usually say nothing; which often forced a person to come up with a better question or thought. For a better idea, his response often was, “that has possibilities.” This was sometimes accompanied by a book, and/or a conversation, that lead to an idea of where to look next. Then… and only if you nailed the idea when you presented it to him, he would give you the response you hoped for, the one that told you, “you really hit it out of the park.”

“That’s interesting.”

Yes, Nathan did not mince words, and he did not use any unnecessary language in his life or in his work; always just enough, and after everyone had said what they had to say. He had a great economy for images and words, but when he used them it was only after looking at things and listening to you. His words and images were helpful and to a positive end; but only if you could recognize it yourself. That I think was the pragmatic part of Nate’s thinking. Many will remember and miss that part about interacting with him.

Again, what a great example of a human my dad was; he was a great father, friend, listener, advocate, organizer, photographer, teacher, husband, grandfather, risk-taker, historian, curator, editor, writer, thinker, mentor, fixer, visionary, great person; Nathan Lyons. He lives through his kindness, his work, his friendships and family. He has left us so much to be happy about. I would like to leave everyone with one more, short anecdote if I may. I say this because it may help put things into perspective today. It has in part for me:

Many years ago Nathan and I were at a funeral service together. It was a traditional service with all the words and all the ceremonies that I think made him uncomfortable. He looked over at me at its conclusion and said to me, with no “uhs” or “uhms”:

“keep it simple… get some friends and family together, have a glass, tell some good stories… enjoy each other’s company.” From that very purposeful statement I can tell you that Nathan did not want anyone fussing over his life nor brooding over the loss of it; So please, if you so choose today; have a glass, tell some good stories, enjoy each other’s company, and please spend time today remembering an interesting man and the meaningful ways that he has been and still is, a part of our lives. Thank you.

by Anne Wilkes-Tucker

Nathan Lyons

Photographer

Cultural Observer

Practitioner and advocate of visual sequencing, text & image, and contextualization

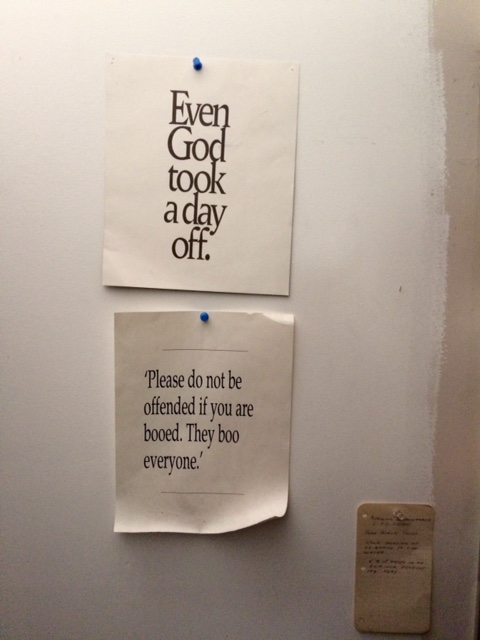

Lover of public epigrams

Read MoreHusbandFather

Grandfather

Visionary

Strategist

Principled administrator

Foil of pomposity and abuses of power

Scholar

Historian

Curator

Champion of young photographers

Professor

Master of the enigmatic challenge

Agent of visually driven thinking

Publisher

Editor

Essayist

Critic

Theorist

Subversive provocateur

Collector

Archivist

Possessor of an acute visual memory

Gentleman

Sage

Friend

Taciturn host

Probing Conversationalist

Mentor, usually over a cup of coffee

Leader of diverse communities and builder of infrastructure

Founder or co-founder of two professional organizations and spark for a third

Founder of the Visual Studies Workshop and its director for 32 years

Winner of 3 honorary doctorates and the Honored Educator Award at SPE

Under recognized for pervasive impact in the creative world

Over six decades Nathan Lyons impacted the professional as well as the personal lifes of many of us.

Former students include

- Directors of museum and alternative spaces

- Curator

- Archivists

- Librarians

- Historians of photography art and culture

- Educators at all levels of photography, visual sociology, film and video

- Critics

- Magazine editors

- Picture editors

- Book artists

- Printmakers

- Filmmakers

- Documentarians

- And most especially, photographers

Nathan passed away on August 31, 2016. Social media instantly filled with tributes and remembrances. Nathan is the reader in my head for everything I’ve written. I am not alone in this. That won’t change. Nor will the challenges issued to many students who won’t know the ways in which their instruction was shaped by their teacher’s teacher.

He perceived what was there and what was missing, imagined what could be, and proceeded to make things happen. His legacy as a photographer, thinker, mentor, friend, and man is profound and embedded in photography’s continuing evolution.

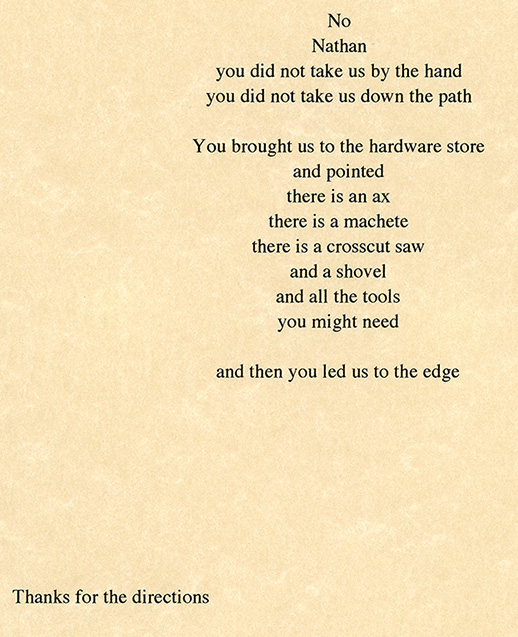

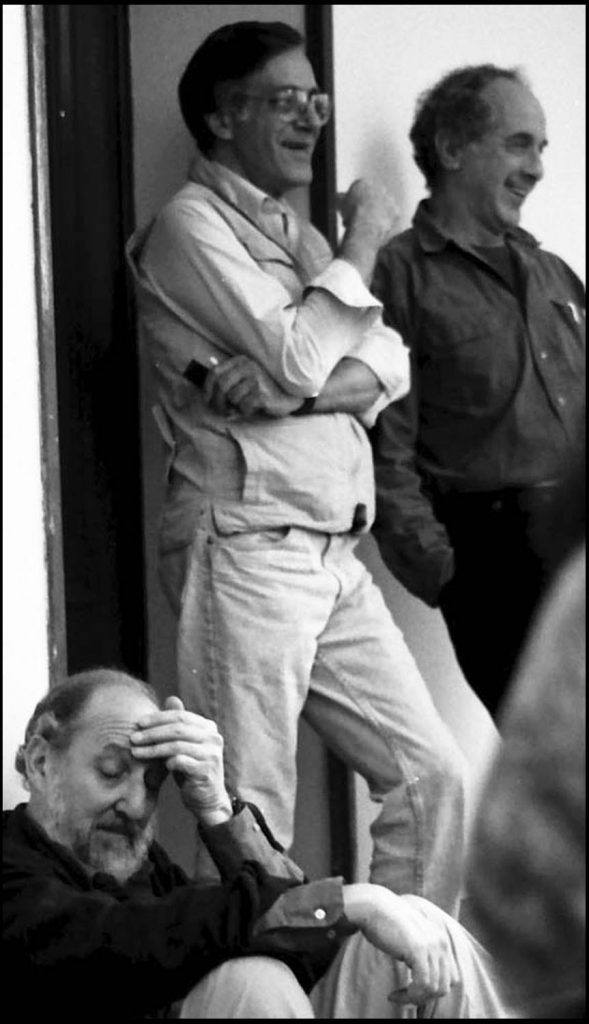

by Mark Klett

Nathan’s passing is a real loss, especially to those of us who studied with him. It’s now been 40 years since I was a grad student, yet I still draw upon the experiences I had working with him. My students will never know Nathan, but they benefit from those lessons.

Read More

In spite of that formative past, some of my fondest memories of Nathan are of spending time with him in more recent years. Sometimes in Rochester, sometimes in Arizona, the conversations, meals and casual time we spent was just as important as those early days at VSW. These were times we spoke as colleagues, though in my mind he would always remain my mentor.While a grad student at the old workshop on Elton Street, I started working in color photography, and at the time it was difficult to do and a bit heretical to the B&W tradition. Nathan was skeptical of this new trend and used to grill me regularly in his seminar about the process and my handling of it. Of course in the end it all worked out for my thesis, but it was clear then that working in color wasn’t going to be his thing anytime soon.

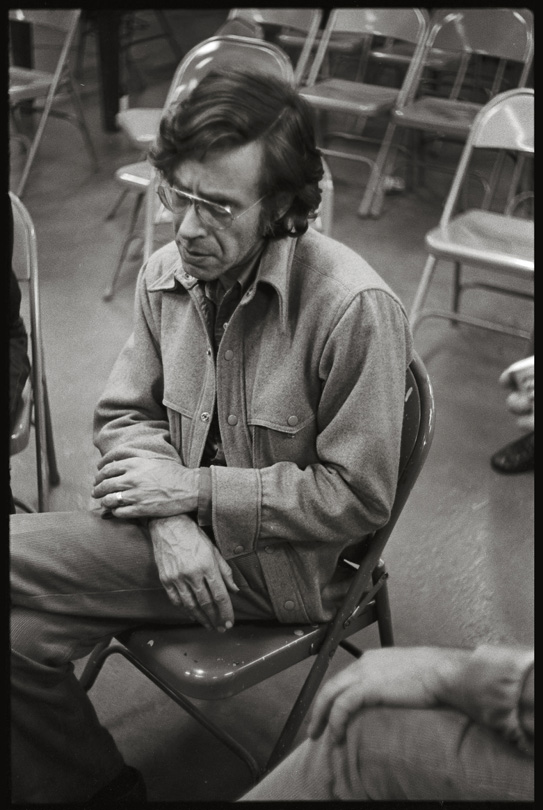

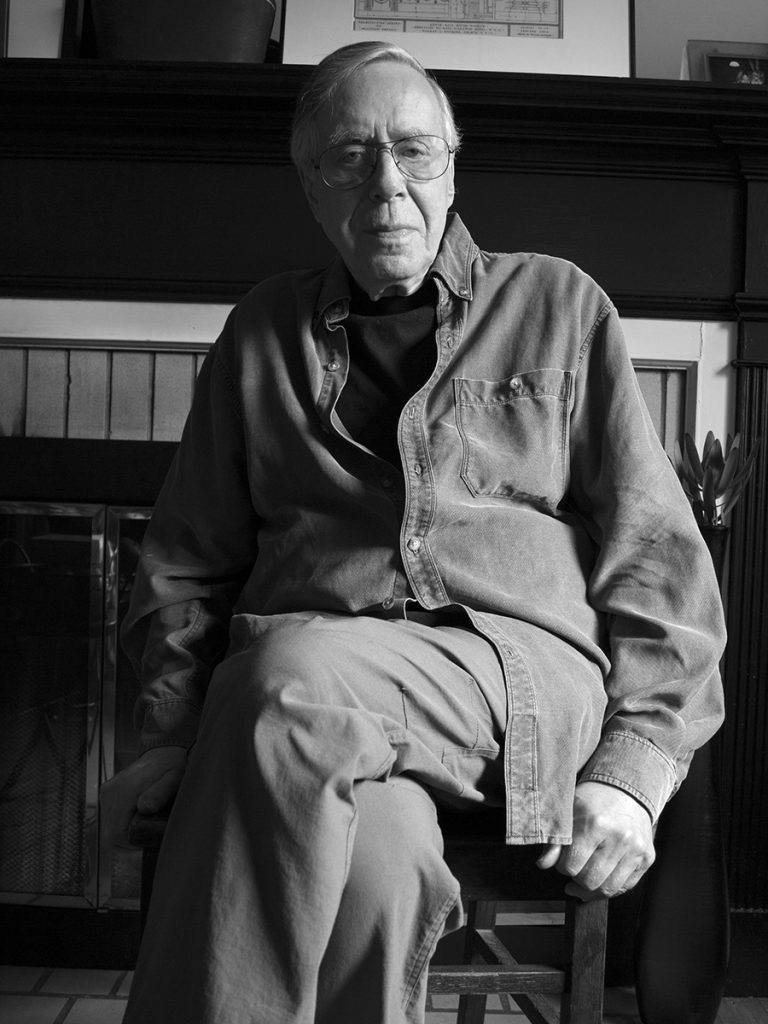

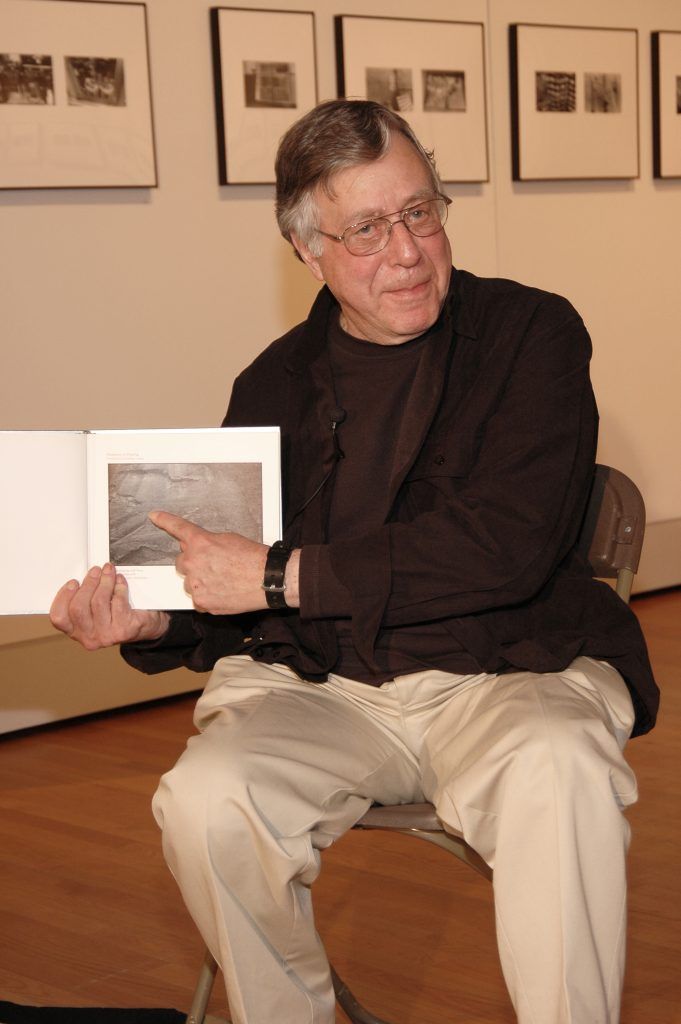

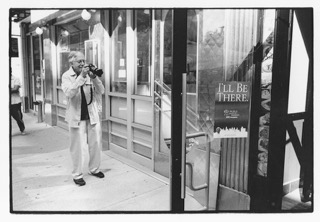

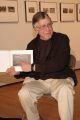

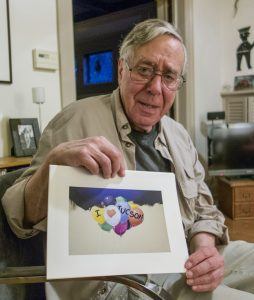

So imagine my surprise when a few years ago Nathan asked if I’d like to see his new color digital work! The photo below was taken in his house while I was looking at his recent prints. I was impressed that at over 80 years of age he was still learning new tricks.

by William S. Johnson

It’s difficult for me to write about Nathan Lyons. I had worked for Nathan at the Workshop during three separate periods, stretched over thirty years, and I saw the warts as well as the wonders in this man who somehow through sheer willpower kept that improbable, even impossible entity–the Visual Studies Workshop–going for so long,

Read Morethrough so many obstacles. The Workshop was a monstrous impossibility; a mashed-together hybrid made up of (at different periods) an alternative art school, a degree-granting visual arts program, an artist’s press, a journal publisher, an art gallery, a traveling exhibitions venue, a video studio, an archive, a library, and more–each of these parts would be enough for most men to wrestle with, but Nathan insisted on them all, and somehow he kept all the balls spinning in the air long enough to keep it all going. Performing miracles from inadequate support bases, staggering from crisis to crisis, its rumored demise somehow always averted, the Workshop was continuously active and contributing to the fields of creative photography, to artist’s book-making, to printmaking, film, videos–in short, to the visual arts. The Workshop has been, over many years, a center of a great deal of creative practice for a great many people.I’m going to relate just one incident that I remember from one of those times. It was the first memory that came to me on hearing that Nathan had just died. The Workshop had moved from its first site on Elton Street to its new location on Prince Street. I was teaching photographic history at the Workshop at the time. Resources were stretched, as usual, and Nathan, after several years of delicate maneuvering, had arranged for a visit from a representative of Rochester’s corporate giant, Eastman Kodak, to investigate the possibility of obtaining some badly needed support. This was, in itself, unusual because Eastman Kodak was not known to be a large supporter of any photographic institutions other than the George Eastman House. And there was the personal history of Nathan’s rupture with the Eastman House’s Board of Directors (a board packed with Kodak officers) which had led to the actual foundation of the Workshop itself. Nevertheless, a meeting had been scheduled, which was to be held in Nathan’s office, followed by a tour of the building.

The night before the meeting a small group of activist students put up a wildcat exhibition depicting Kodak’s industrial pollution statistics in Rochester, in the hallway in front of Nathan’s office, to be found on opening the building in the morning.

To my way of thinking, this was a thoughtless, useless, and arrogant act. It achieved nothing, except to absolutely guarantee that whatever tenuous chance the Workshop might have had of getting some badly needed support from Kodak would be squashed. This must have been a moment of tremendous pressure on Nathan–to support the right of those students to express their point of view, however mistimed, however inappropriate; or to give in to the impulse to remove the show before the official arrived–an impulse which had to have been powerful, almost overwhelming.

Nathan left the exhibit up and then went through the fruitless charade of the visiting tour. Of course, no support ever materialized from Kodak. A week or so later the exhibition disappeared as anonymously as it had arrived. As far as I know, Nathan never took any steps to identify or in any way remonstrate with the students who were responsible.

So–a quiet decision to support the right of freedom of expression occurring in the face of a very real pressure, and having very real consequences, was taken by Nathan so seamlessly within the everyday workings of the institution that it was pretty much overlooked by everyone at the time. For me, I found this to be an act of moral integrity, and a demonstration of the character of the man who fought so quietly and so relentlessly for the arts during his long and fruitful life.

by Ellen Manchester

As a young person with an interest in photography, but limited talent, both Beaumont Newhall and John Szarkowski recommended that I check out a new program started by Nathan Lyons (after he got fired from George Eastman House) in Rochester. So I enrolled in VSW in their 2nd year of operation. What a ride it was!

Read MoreFour amazing years of intense seminars, new projects (“Ellen let’s get a library started, and learn the Library of Congress system so we can do it right.”) Library of Congress catalog cards were typed then Xeroxed one by one on Joan’s huge Xerox machine in the loft of VSW.

Nathan was loving, but always tough—pushing one hard but with a unique sense of humor—”Ellen, Robert Frank needs a place to rest before his talk, could he take a nap at your apartment?” “Did you archive the ring in the bathtub after he left?”

So many more stories of the tremendous influence he had on our lives, inspiring us all to stay intensely curious about the world. I will miss him so much. RIP

by Robbie McClaran

When I first arrived at the Visual Studies Workshop in late summer of 1976, I was wide eyed, a bit naïve, an eager young sponge ready to soak in everything to come. I had enrolled in what was called the “Workshop Program” which was a full time non-credit course of study that was the same classes offered to the MFA program. I was a bit younger and less experienced than most of my classmates, having foregone a traditional four-year undergraduate program. Those first few days I began to wonder if I was over my head.

Read MoreThe Workshop had already gained the reputation as the single most vital program in the country for artists working in photographic media and stories of Nathan’s classes were legendary. He did not disappoint. I often left his class confused, baffled even, over what we had discussed. He was clearly operating on a different level, a level way over my head.

Back at my apartment I would spend hours pouring over Notations in Passing, looking for insights, clues. Each viewing taught me something new, a fresh discovery.

He could be maddening to a student looking for a shortcut, or to be told what was right or wrong about an image. These were not classes about how to take good pictures. I recall that Nathan didn’t put much importance on an individual image. He taught us to look at groups of images, study contact sheets and engage with them, to try and understand what the body of work was saying. Images that popped out were either the good ones, or the bad ones that didn’t fit. Which was which was up for us to decide.

Over the years those discussions and lessons would often emerge from the deep recesses of my mind, ideas about photographs as language, how images can have conversations with each other, and how different combinations or sequences of the same group of images can tell different stories. These ideas and many others have stayed with me and have informed the direction of my work throughout my career.

When I say I studied with Nathan, I mean much more than simply taking classes with him. I mean I studied and worked with an amazing collection of artists and teachers. People like Dave Heath, John Wood, Keith Smith, Bill Johnson, Michael Bishop, and of course the amazing Joan Lyons. There was a near constant parade of visiting artists dropping in to talk about their work, or just hang out. I worked alongside an equally impressive group of fellow students who went on to do important vital work in the field of photography; curators, museum directors, photo editors, and of course artists. The names read like a who’s who of contemporary photography.

And the one common thread, the reason all of these people were there at the Visual Studies Workshop was because Nathan had brought them there.

My few years working, studying, creating, learning, at the Visual Studies Workshop changed the course of my life. The experience opened doors and possibilities I never imagined existed for a boy from the delta of Arkansas.

I’ve been back to Rochester only a couple of times, once in the late 1990s when I was invited to exhibit my work in the gallery (one of my life’s greatest honors), and once for Nathan’s retirement celebration. Each visit, I witnessed how the Workshop had matured over the years, not just survived, but had thrived and continued to carry out the mission Nathan had envisioned. It has done so by the sheer force of Nathan’s will and the work of those he inspired to work alongside him, as well as those to follow in his giant footsteps.

My sincerest condolences to Joan, Elizabeth, Ethan, David and to everyone who mourns his passing. Through so many people he taught, mentored, and inspired, Nathan’s life’s work, and his spirit will endure. I can think of no greater testament to a person.

Thank you Nathan.

by Arthur Nager

Nathan Lyons had a great impact on my life and career and it began when he accepted my application to join one of the early VSW classes in 1972. As a self-taught photographer with a BA in History and Psychology I applied without the usual pedigree of a Fine Art degree. It might have been my work as a museum intern at the George Eastman House or my willingness to forgo an

Read Moreacademic career for one less defined or predicable that influenced him – it certainly wasn’t my carpentry skills. But I will forever be indebted to him for this first vote of confidence and for a second vote when he recommended me for a teaching internship at the Center of the Eye in Aspen. Nathan’s style of teaching did not focus on the validation of one’s work as good or bad – instead he conveyed that it was the overall body of work that mattered. This approach to the medium provided the framework for how I began teaching and continued through my years directing a photography program on the University level. Nathan served as the model for how to create a community, foster dialogue about photography and how to communicate what photography could be to a broad audience. Through his example he not only influenced those who went on to pursue careers in the field, but those who pursued other interests. I would be remiss to not mention the fact that I remain forever in his debt for bringing together many of the photographers that I came to meet during the early VSW days, some of whom continued as friends. In particular, I would mention my advisor Syl Labrot who was a great teacher and remained a great influence and friend for many years. 1972 was a long time ago, but it seems like only yesterday thanks to Nathan – he will be missed but remembered by all who had the privilege to know him.by Bill McKenzie

My warmest memories of Nathan are that he was such a kind and generous man. And he would throw me pitches I could hit!