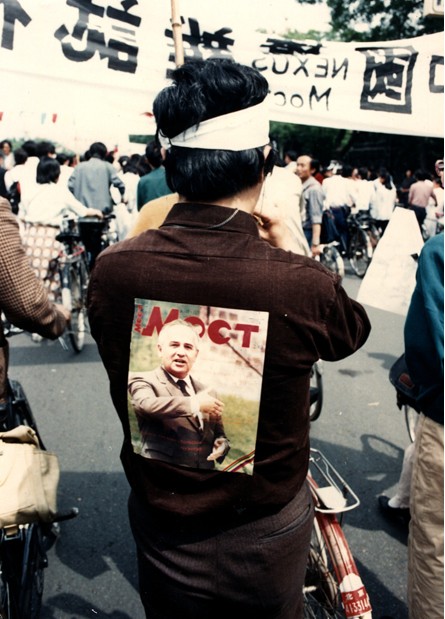

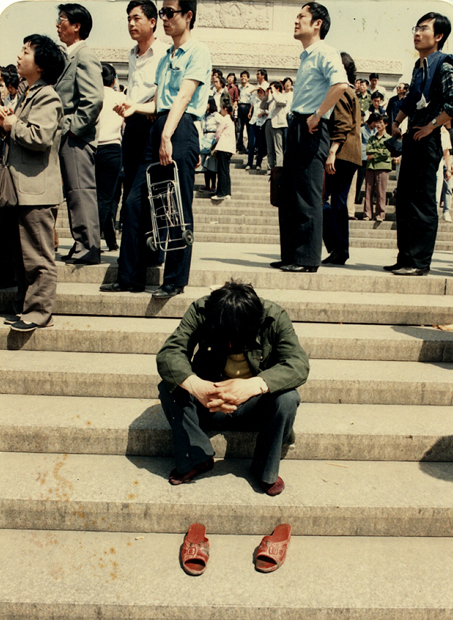

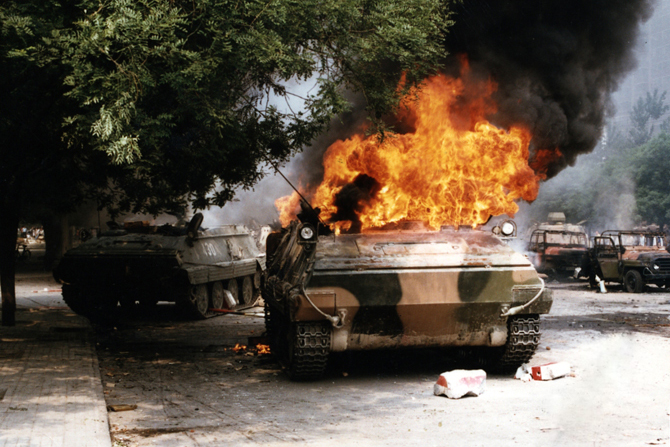

The 20th anniversary of the Chinese pro-democracy movement has been commemorated around the world. This exhibition of Khiang Hei’s photographs is unique for the powerful visual records it presents. Hei was a witness to history. His photographs covered the main course of the movement in Beijing in the spring of 1989. They captured the epic drama in Tiananmen Square—the million-strong street demonstrations, the hunger strikers, and students huddling in colorful tents determined to reclaim Tiananmen as a space of the people. There were moments of quietness and silence, as well as scenes of passionate speech-making, flag-waving crowds, and beautiful children looking on with wide-open eyes. As the protests escalated, bright portraits of solidarity, hope, and revolutionary festivity gave way to dark images of pain and exhaustion until ghastly pictures of desolate streets, abandoned bicycles, burning tanks, and death marked the terrible ending of that short but singular moment in Chinese history. Hei’s photographs take viewers back to the joys and sorrows of that extraordinary time.

Yet despite an officially instituted amnesia, the movement has not been forgotten in China. A Tiananmen Mothers movement, organized by parents whose loved ones were killed or wounded on June Fourth, 1989, has been pressing the Chinese government to publicly acknowledge its culpability and apologize to the victims and their families. Original participants have formed communities of memory. Intellectuals have never ceased reflecting on the meaning of the movement.

From a longer historical perspective, the popular movement in 1989 marked the peak of the enlightenment project in modern China. Chinese struggles for enlightenment started in the iconic May Fourth movement in 1919. Like the movement in 1989, it was led by students and it started in Tiananmen Square. It celebrated the European Enlightenment ideals of democracy and science, even as it attacked western imperialism and Confucian culture. The protesters in 1989 proclaimed themselves true heirs of the May Fourth spirit and fought for the same ideals.

The military crackdown on June Fourth, 1989, shattered their dreams. Disillusionment and cynicism permeated Chinese society in the wake of the repression. For the sake of self-redemption if nothing else, the senior Communist party leader Deng Xiaoping pushed forward the party’s reform agenda in 1992. China has since rapidly transformed into a market economy. In recent years, a “China miracle” is suddenly all the buzz in the mass media.

It is a miracle with severe costs, however. As China maintains high levels of economic growth, it faces problems of social polarization, corruption, and environmental degradation on an unprecedented scale. In response, a new wave of popular protest and social activism is sweeping across China. Tens of thousands of protests and petitions happen every year, involving people from all walks of life.

Compared with the protests in 1989, however, the goals of this new activism are more concrete and down to earth, the means are more moderate, and the issues are more diverse. Many new issues have taken center stage, ranging from environmental protection and HIV/AIDS to marginalized social groups, alternative lifestyles, anti-discrimination, legal aid, education for migrants and their children, and domestic violence. Freedom and democracy are still inspiring ideals, yet activists begin to use more moderate tactics. They invoke the law in their struggles to protect citizens’ rights, adopt non-confrontational forms of action, make skilful use of the Internet, and emphasize the building of an organizational base.

The most important forms of China’s new citizen activism are probably new types of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and online activism. NGOs first appeared in the mid-1990s. Now numbering in the thousands, they conduct public forums, undertake community projects, and launch media campaigns, but rarely organize street protests. To maintain a legitimate status and some degree of independence, they avoid direct confrontations with government authorities and cultivate cooperative ties with state officials.

Online activism is primarily discursive and symbolic, involving verbal protest in online forums, the hosting of campaign websites, and online signature petitions. Speed and ease of access make the Internet an especially effective forum for exposing corruption and airing grievances. Cartoons, online videos, digital images, and other artistic forms are used to mock power and authority or express dissent. Despite (and often in response to) government censorship of the Internet, the most creative and penetrating of these cultural forms spread online like wildfire and become national media events. Many cases have shown unequivocally that Chinese citizens are effectively tapping the power of the Internet to achieve popular contention.

Thus in the two decades since 1989, protests have increased in frequency, but have assumed new forms. Large-scale mobilization of the 1989 style has not been repeated. In urban China, moderation, flexibility, and non-confrontation are the dominant style of the new citizen activism. This seemingly prosaic style of activism, however, is effective in its own ways. It has led to changes and shifts in government behavior and policies. Perhaps more importantly, the flourishing of this new activism both reflects and raises people’s consciousness about what they can do and must do to defend their rights. China’s political environment continues to constrain activism. Although Chinese society is more open than ever before, public discussions about many issues (such as the history of June Fourth) are still off limits. NGOs may be forced to close down for political reasons. But the flexible style of the new citizen activism means that it is here to stay.

How to account for the rise of this new citizen activism in China? One obvious reason is that Chinese society and politics have undergone profound change since 1989. In the middle of economic growth, the rural population is left behind. And because of unsustainable approaches to development, the environment is seriously damaged. The privatization of large state-owned enterprises has caused serious unemployment and led to frequent labor strikes. Even the increasing size of the urban middle class is a mixed blessing. With growing private ownership of houses, apartments, and automobiles, the middle class is raising its demand for the rule of law and the protection of their property and civil rights. The urban middle class is the main force in NGO-led activism.

The development of the Internet and mobile phones facilitates citizen activism. China established Internet connectivity in 1994. Since then, the number of Internet users has increased dramatically, exceeding 300 million by July 2009. This is the largest Internet population in the world. A crucial factor underlying the rapid development of the Internet in China is that the Internet meets urgent social needs—the needs for information, communication, social connection, and civic organizing. The growth of the Internet in China has paralleled the growth of civil society.

Globalization is another important factor. The interactions between globalization and local cultures are complex, often involving mutual learning. In the field of citizen activism, the influences of international NGOs on indigenous citizen groups are evident. Hundreds of international NGOs have set up offices or run projects in China. Like domestic NGOs, they work on a broad range of issues. Greenpeace, for example, has an active office in Beijing and has waged several successful media campaigns. These international NGOs collaborate with Chinese NGOs, offer grants to them, and provide training workshops and other forms of capacity building. They introduce global discourses of citizen action and international cultures of civic organizing.

Members of the Tiananmen generation are active in this new wave of activism. The fateful experiences in 1989 gave the participants the collective identity of a new political generation—the Tiananmen generation. This generational identity carries with it the historical consciousness of a repressed revolutionary movement and helps to sustain a level of civic participation. The political experiences people gained and the social ties they forged in 1989 serve them well as some of them assume new roles as environmentalists, human rights activists, legal activists, organizers of home-owner associations, and internet activists. Naturally, the vast majority of the generation have settled back to the routines of ordinary life, but in China today, everyday life is no less a site of political activism than Tiananmen Square. Much like the global 1960s generation, the Tiananmen generation has not relinquished its political passions, but has transformed them into new forms.

As China’s post-1989 cohort comes of age, a process of generational learning is taking place. Due to the lack of history education, the 1990s cohort may know little about what transpired in 1989. But many young people are eager to learn that history. They are not as politically cynical or indifferent to social justice as they are sometimes made to appear. This new generation proved itself capable of civic engagement and activism in the outpouring of volunteerism after the earthquakes in Sichuan province last year. Some of them are consciously learning from the political experiences of their parents’ generation.

The same conditions that give rise to the new citizen activism explain its relationship to 1989. The rise of a middle class, the Internet, the cultures of globalization, the coming-of-age of a younger generation—all these shape contemporary activism. Adapting to new conditions, Chinese activists have fashioned new identities and new forms of action. In the age of the Internet, they are both organized and scattered, both connected and decentralized. In dispersion as in solidarity, they are a formidable force of social change. Fighting for small gains in everyday struggles, they have not lost sight of the bigger visions of the pro-democracy movement in 1989, just as the generation of 1989 had upheld the visions of their May Fourth predecessors.

By paying tribute to the heroes of 1989 and to the Tiananmen generation, this exhibition commemorates a great tradition and celebrates the courage of the common people in their struggles for a better world. The use of multi-media formats, including an exhibition web site, is the most fitting expression of the creativity of the new citizen activism that has emerged in China since 1989.

Guobin Yang is an Associate Professor in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Cultures at Barnard College, Columbia University. He is also a faculty in the Weatherhead East Asian Institute and an affiliated faculty in the Department of Sociology of Columbia University. He has published on a wide range of social issues in China, including the internet and civil society, environmental NGOs, the 1989 student movement, the Red Guard Movement, and collective memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. His books includeThe Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online (Columbia University Press, June 2009), Re-Envisioning the Chinese Revolution: The Politics and Poetics of Collective Memories in Reform China (edited with Ching-Kwan Lee, 2007), China’s Red Guard Generation: Loyalty, Dissent, and Nostalgia, 1966-1999 (under contract, Columbia University Press).